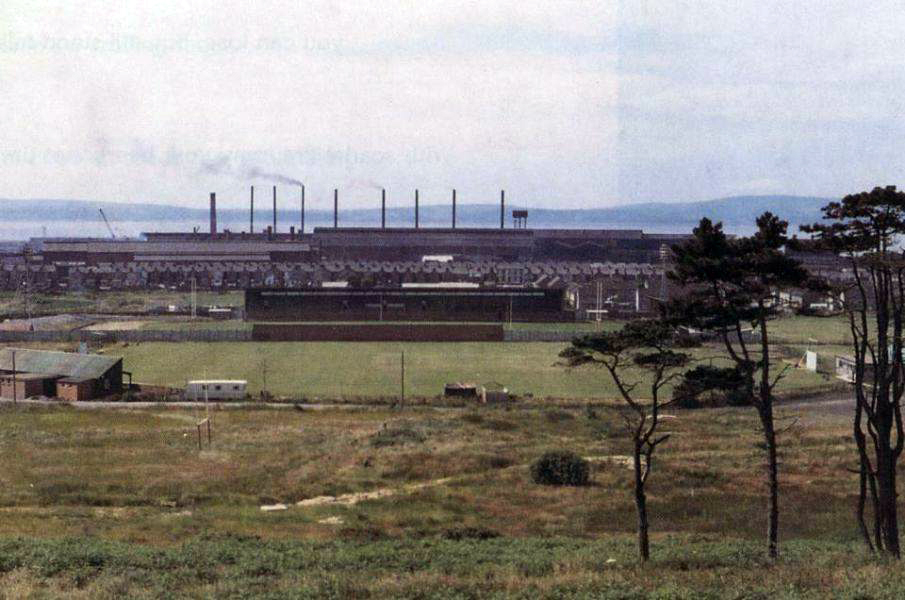

‘Why do we still send humans down mines?’ Because of a marketable product and mass unemployment. And no red tape.

In English ‘gleision’ means ‘whey’ – as in curds and. This will probably describe the manner in which the local spring seeps out of the earth, or possibly the taste or colour of the water. And ‘gleisiad’ are young salmon. But whatever the poetry, it is all about water. The entire area and culture is shaped by water. But even now, after everything it has done, it is still profitable to ignore it.

The news-feeds and politicians are very quick to invoke the ‘community spirit’ of the coalfieds, though none has yet gone as far as mentioning Senghenydd or Aberfan. This is to glorify these dirty, unnecessary deaths and excuse the causes. This hardy, stoical, almost primordial Welsh identity is what the media plug into for want of any other, especially in the industrial south.

In truth, the Welsh identity is as elusive to the Welsh themselves as to the rest of the world. Economic collapse and the failure of regeneration has almost guaranteed this insecurity. The danger therefore exists of cultural feedback, whereby Wales defines itself by its stereotype, which could lead more young men to return underground in order to retain some sense of group identity, and with it their personal dignity – the original class dilemma rearing its head in another direction.

Those tempted should remember the fatalistic old collier’s folk ditty, in the traditional Wenglish of the valleys.

The tragedy of the four dead men was, inevitably, less real to me than the issues it raises. The immediate lapse into How green was My bloody Valley and Huw Edwards invoking Senghenhydd with bloody Calon Lan playing in the background made me seethe with anger and embarrassment. The heroic, pious, oaken colliers firing the turbines of the Royal Navy. Acknowledged now as the pit-props and ponies of Empire. And their precious, quaint, black-shawled, slow black, coal black, minor chord community choruses of unintelligible pain.. Very telegenic. Community my arse. It makes me want to puke. The reality is that many small towns in post-industrial south wales are no better than people traps. Which is why when there is a chance for their young men, especially, to earn some cash, and play some sort of role, the danger is immaterial. The ability to claim a clear identity is worth as much as the pay. As is the undoubted and vital communal bond between miners. Fellowship.

But Britannia doesn’t rule the waves any more, even if the price of anthracite is nice and high at the moment. And so the collier today, especially in the kind of casual drift mine I used to play in as a little boy, is little more than a paid member of a historical re-enactment society. He is not the hero of anyone’s fantasies. The Welsh working class, which it took the British army to quell – more than once – and which went on to create the National Health Service, is brought to this ridiculous parody of itself, like an ancient sacrifice to the Spring.